Since the days of his cherished column on ESPN’s Page 2, Bill Simmons has enjoyed deliberating over whether the 1996 Tom Cruise vehicle Jerry Maguire is a “sports movie” or a “chick flick.”

“This is the Roe vs. Wade of ‘sports movie/chick flick’ debates,” he adamantly proclaimed back in 2002, before ultimately deciding on the former:

“Some guys are adamant that this qualifies as a chick flick, and hell, they’re probably right to a degree.

But there’s too much sports stuff crammed in here, and all the sports-related stuff is absolutely essential to the movie.”

However, in more recent years, he’s waffled on that original verdict…

“You could make a really good case that it’s the best rom-com ever made.

So what if Rod Tidwell is the best-written athlete character in Hollywood history? It’s still a rom-com.”

A few times, as a matter of fact…

“This was a movie that was set in sports but isn’t a sports movie.”

To the point of resigned indecisiveness…

“Can it be both? I think it can be both. I’m fine with it being both.”

But, in Mr. Simmons’ defense, I believe the reason he remains “so conflicted” about this, to quote his old Page 2 editor Kevin Jackson, is because Jerry Maguire is, in fact, neither a sports movie nor a rom-com.

Like The Big Short and The Big Lebowski, The Wolf of Wall Street and Wayne’s World, Baseketball and Billy Madison, Jerry Maguire is really a film about…

Lost in the hellos one might have been had at, the dubious facts about the human head, and the discovery of “quan” is a 25-page memo mission statement that kicks off our hero’s journey:

The result of a breakdown breakthrough, The Things We Think and Do Not Say was a brutally honest channeling of the late, great Dicky Fox —

— that gave voice to what everyone in Mr. Maguire’s industry had been noticing for years yet not saying a word about:

“In the quest for the big dollars, a lot of the little things were going wrong…and lately, it’s gotten worse.”

Thanks to Cameron Crowe’s official site, The Uncool, you can actually read the entirety of that 25-page “love letter to a business I truly love,” as Maguire calls it, and palpably feel the “cruel wind blowing through [their] business.”

If, though, I can impart just one excerpt on your waning attention, let it be the following:

It is time to not second guess, to move forward, to make mistakes if we have to, but to do it with a greater good in mind.

Because it is in that spirit I write this love letter to the media industry I truly love.

And because I believe in it, and the people who compose it, and the beautiful gift-and-curse power it wields.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit this thing may, as Mr. Maguire puts, get somewhat “touchy feely,” but I was also once told by an exquisite woman named Dorothy Boyd that “in this day and age, optimism like that is a revolutionary act.”

Therefore, starting with an attempt to solve the trickle-down pickle and going all the way through to a high-minded argument for The Denver Post’s own strain of weed, allow me to propose a new direction in which we as an industry can move forward — making mistakes if we have to, but doing so with a greater good in mind.

Of course, it goes without saying this memo mission statement may not be the answer to all our worries.

However, to borrow from the sage Rod Tidwell, “it’s an answer.”

And if anybody wants to help me with it, this could be the ground floor of something real, and fun, and inspiring, and true in this godforsaken business.

So…

Who’s coming with me?

Table of Contents:

I. The Trickle-Down Pickle

II. A Patronizing Solution

III. Likely Ramifications & Lighthearted Ruminating

IV. In Conclusion…

I. The Trickle-Down Pickle

1979 saw all subspecies of elephant emerge from the political high grass in hopes of stampeding a vulnerable President Carter.

Distracted from his campaign by the threat of escalating gas prices, increased economic stagflation, the Iran hostage crisis, and a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the stubborn-as-a-mule Democratic incumbent seemed poised to be trampled by whichever ambitious pachyderm secured the chance to try.

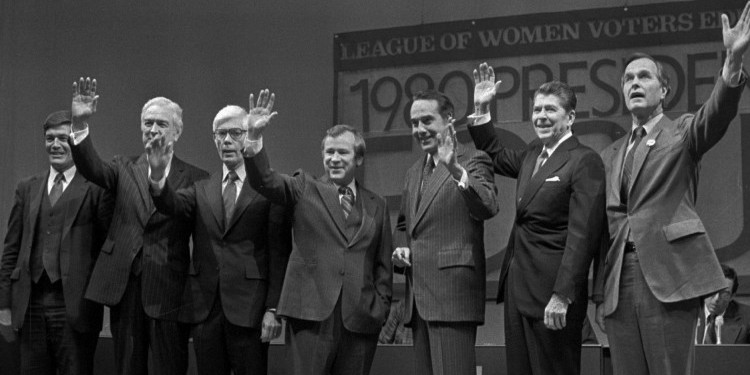

Hence, in addition to Ronald Reagan — the Hollywood actor turned politician who’d tried unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination the two elections prior — Senators Howard Baker, Bob Dole, and Lowell Weicker; Representatives John Anderson and Philip Crane; former Texas governor John Connally; and former director of the CIA George H. W. Bush all eventually materialized to raise their mighty trunks…

Considering he had nearly beaten then-incumbent Gerald Ford four years earlier, former governor Reagan was the early favorite to win the nomination; his chief strategist John Sears going so far as to implement an “above the fray” strategy early on.

However, while the charismatic Californian was sitting out the multi-candidate forums and straw polls of late 1979, George H. W. Bush, the practical, diligent Texan, attended every one of those grueling “cattle calls” — and then he started winning them.

After pulling off a stunning upset in the vital Iowa straw poll of late January, he even began declaring that he had captured “The Big Mo.”

Hubris like that doesn’t go unpunished though, as a month later, on a cold February night in Nashua, Bush’s snowballing momentum was stopped dead in its tracks by Ronald Reagan’s fiery claim of ownership of a debate microphone:

Nevertheless, the former CIA Director trudged on for three more months, throwing frosty jabs at the presumptive winner every step of the way.

The most memorable of these was delivered on April 10th, 1980 to a lecture hall at Carnegie Mellon University in which Bush positively lambasted the supply-side economics we would later portmanteau with the president who would soon implement them — proffering for the first time a term that’s been used by generations of Keynes defenders ever since:

This was his name for those trickle-down policies that were first attempted back in the early 1890s under the name the “Horse and Sparrow” theory…

“If you feed the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows.”

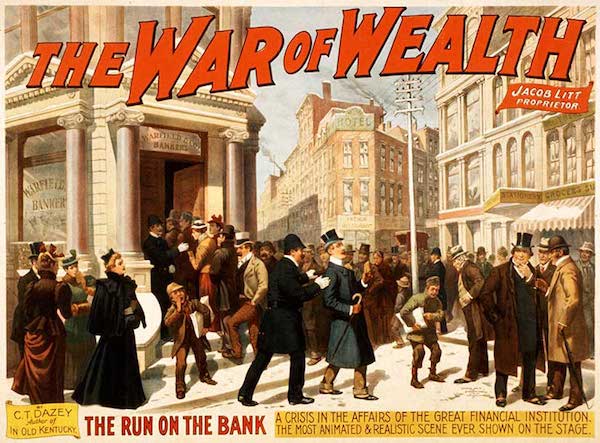

…and which helped contribute to the Panic of 1896:

Those same “free enterprise” philosophies that have proven time and time again to be inegalitarian at best, plutocratic at worst…

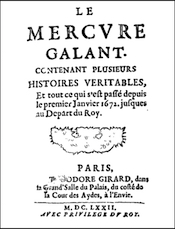

…and which the majority of media companies, stuck in the days of Le Mercure de France, continue to imprudently impose on their constituents, seemingly oblivious to the panic to which they’re contributing.

To be sure, a filter-down approach may make sense for most industries, where the ignoble sparrows need their preceding horses’ metabolisms so they humbly accept their place behind them.

However, it’s become unavoidably clear to anyone with a bird’s-eye view of the road that the well-fed thoroughbreds we in the media industry have solely relied upon for our survival have been fundamentally, irreversibly exposed over the past decade as lamely inefficient, to the point of near obsolescence.

One can see it in the escalating flurry of writers and journalists and editors and researchers and graphic designers and photographers — ruffled over “pay disparity among employees doing similar jobs…low wages…and no clear way in which raises are standardized or tied to measurable job performance” — attempting to unionize in some form or another (with varying success); the huddled flocks finally turning against the mulish holding companies and media conglomerates and billionaire owners who aren’t letting enough of their oats pass through.

If this is empty, this doesn’t matter. — Dicky Fox

An exercise in kinesthetic acquisition: go to GlassDoor.com and type in your favorite outlet, whether it’s The New Republic or the The New York Times, then sort the salaries listed from highest to lowest.

You’ll soon notice that, for the most part, to have “Writer” or “Reporter” or “Journalist” affixed to one’s title means a vulturous life near the lower five-figure end of that trail; behind the coltish “Marketing Managers” and “Account Managers” and “Product Managers”; a world away from the prized “Advertising Production Representatives” and “Advertising Sales Directors” and “Advertising Vice Presidents.”

When Radhika Jones took over pole position at Vanity Fair in November of last year, she was tragically forced by Condé Nast to cut overall costs at the magazine by a staggering 30 percent.

But, as Financial Times pointed out at the time, Ms. Jones’ remuneration package was nonetheless “about $500,000 a year.”

No one said winning was cheap. — J.M.

In all fairness, that was “substantially less than [former Editor-in-Chief Graydon] Carter, who was paid about $2m a year plus a generous perks package that included use of a private plane.”

Not to yada yada over too much of the other occupational crap the typical salaried writer/journalist/editor/etc. has to ingest on a daily basis to survive, but I trust if you’ve made it this far you either know from experience or can imagine what it’s like working at one of the smaller — and thus more desperate — outlets, whose rapidly evaporating revenue streams have led to a rationing of oats heretofore unforeseen.

If not, in short: the take-home pay is laughable (with “women and minority staffers [earning] significantly less than their male and white counterparts”), the workload is unbearable, and the satisfaction that comes with knowing you did a job well done has become the stuff of old wives’ tales.

More succinctly:

It is an up-at-dawn, pride-swallowing siege that I will never fully tell you about. — J.M.

It is a ceaseless crossfire of headlines like Deadspin’s “How SB Nation Profits Off An Army Of Exploited Workers” and Splinter’s “Mic Lays Off Dozens Just a Week After Promising Not To” and Jezebel’s “Hey, Remember How Much Bustle Founder Bryan Goldberg Sucks?” (a followup to the Valleywag classic “Who Gave This Asshole $6.5 Million to Launch a Bro-Tastic Lady Site?”).

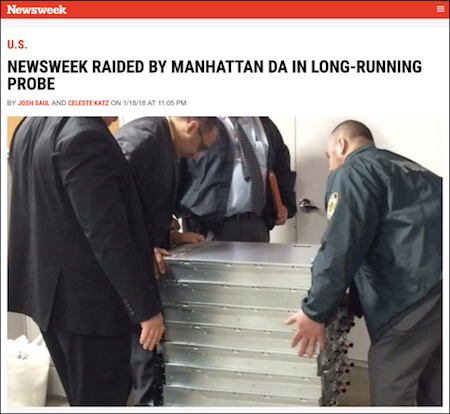

It is an incessant sequence of scandals, like the one at Vice where, to pull from an NYT headline, “cutting-edge media met old-school sexual harassment,” or the one at Newsweek where their top journalists and Editor-in-Chief were unceremoniously fired for investigating their parent company’s massive financial crimes after the Manhattan district attorney raided their office last January:

It is, in the words of another Newsweek editor, “bullshit.”

Nevertheless, save for the few lone kestrels who’ve refused domestication, this life of daily debasement still beats trying to survive on one’s own as a full-time, sans-benefits freelancer.

Resorting to full on media mercenarism, those unaffiliated hirelings are often bound to a consumptive pen-to-mouth existence that by its very nature demands a sense of prudent detachment…

Back in 2014, one of my favorite freelancers in the game today, Luke O’Neil, made a handy list of what he, an esteemed writer who’s been doing this for a decade, got paid by various multi-million dollar media outlets, and to call it disheartening is an understatement of subterranean proportions:

- The Boston Globe: roughly 50 cents a word usually, $75-150 shorter, $250-$600 for feature

- The Wall Street Journal: $1 a word print

- The Washington Post: $250 web

- The New Republic: $200-250 web

- Slate $200-300

- Gawker: $100 freelance post, $150 a day of blogging (6-8 posts)

- Vice: $50-150 web

- MTV: $50 blog post

- Interview Magazine: $20 web

Indeed, math may not be my strongest suit, but one doesn’t need a Google Sheet to know those sorts of numbers add up to a ruthless, relentless life in the bottom tax brackets.

I can tell you that for a freelancer to earn $50,390 — the current median wage for college graduates — they would need to dream up, pitch (successfully), report on, write, edit, publish, and be paid an average of $1 per word for ~4,200 words per month, while at the same time fending off the murder of busking crows who’ll happily trade thousands of words in exchange for a measly byline or crummy internship.

Or concert tickets.

Meanwhile the portly broomtails lumber up ahead in the distance, paying no mind to the panicked squabbling behind them.

It’s just the birds, falling all over themselves for the leftovers…

II. A Patronizing Solution

The Guardian is a fantastic beast.

As the following spiffy video explains, unlike most other major outlets that are presided over by some sort of secret board of shadowy figures, the Guardian’s parent company instead “has only one shareholder: The Scott Trust.”

Established in 1936 by then-Manchester Guardian owner John Scott, it was created “to ensure the independence of the newspaper and the continuance of the journalistic principles of his father,” the great CP Scott, whose centenary essay for the paper from 1921 remains a stirring ode to the industry.

A particularly affecting section:

A newspaper has two sides to it. It is a business, like any other, and has to pay in the material sense in order to live. But it is much more than a business; it is an institution; it reflects and it influences the life of a whole community; it may affect even wider destinies.

It is, in its way, an instrument of government. It plays on the minds and consciences of men. It may educate, stimulate, assist, or it may do the opposite.

It has, therefore, a moral as well as a material existence, and its character and influence are in the main determined by the balance of these two forces.

It may make profit or power its first object, or it may conceive itself as fulfilling a higher and more exacting function.

Almost a century after that letter’s publishing, the Scott Trust remains committed to its central objective — “to secure the financial and editorial independence of the Guardian in perpetuity” — and does its best to honor the elder Scott’s century-old assertion that “one of the virtues, perhaps almost the chief virtue, of a newspaper is its independence.”

As such, the Guardian is the only British national daily to conduct an annual social, ethical and environmental audit in which an independent external auditor examines the company’s behavior, and the only British national daily to employ an internal ombudsman. It continues to reinvest all of its profits back into its journalism and recognizes that “whatever [a newspaper’s] position or character, at least it should have a soul of its own.”

We are sometimes as important as priests or poets, but until we dedicate ourselves to worthier goals than getting an illegal phone number, we are poets of emptiness. — J.M.

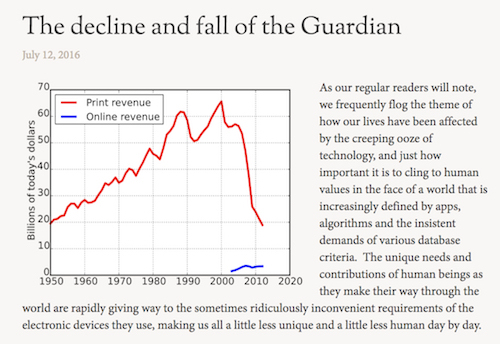

None of that, however, stopped the Guardian Media Group from absolutely hemorrhaging money for over a decade, from 2006-2016…

For three consecutive years, from 2009 to 2012, the paper lost £100,000 a day.

So, one fateful January morning in 2016, the publishers, with nothing else to lose, announced a bold plan for the Guardian Media Group to break even at an operating level by 2019.

“Designed to safeguard the long-term future of the Guardian’s award-winning editorial platforms,” the three-year plan involved cutting 20 percent of the company’s overall costs (including some 300 staff), moving the Guardian and Observer from a Berliner newspaper format to a cost-saving tabloid format, and relaunching “an enhanced membership offer with the aim of doubling reader revenues.”

Which included the adoption of a fairly novel approach to revenue acquisition, for a major outlet…

Straight up asking their readers to give them money:

And wouldn’t you know it? It worked.

It bloody worked.

Guardian News & Media recently announced that it is on track to break even this year, having raised nearly £100 million in reader revenue since implementing its audacious tip jar-centric plan.

Not only is the Guardian website averaging 155 million readers per month (up from 140 million the year before), the Guardian and Observer now tout a combined 570,000 regular supporters and have received over 375,000 one-off contributions from readers in the past 12 months alone.

In fact, the Guardian Media Group reported back in July it now earns more money from its digital operations than from its print newspaper — “aided by increased support from readers making online contributions” — with reader revenues representing more than half of their total revenues.

As Anna Bateson, who was appointed as the Guardian’s first ever chief customer officer in 2017, recently attested, asking for contributions “is as much about what the reader is reading at that moment” as it is capitalizing on built-up trust.

There is, evidently, “a third way to pay for quality journalism.”

And the Guardian’s unpredicted success isn’t some bizarre English phenomenon like Brexit, I swear.

The Guardian Media Group reported “more than half of the Guardian’s global revenue from one-off contributions came from the U.S.,” with 230,000 of their 300,000 American supporters donating one-off contributions as opposed to investing in a recurring subscription.

If anything, “Americans are more inclined to give,” says Evelyn Webster, who became CEO of the Guardian’s US and Australia operations in December.

“The cultural act of giving isn’t necessarily transactional. People tend to give without any expectation of anything in return.”

Forget the dance.

Focus.

Learn who these people are.

That is the stuff of your relationships.

That is what will matter. — J.M.

At this very moment, people around the world are already giving to:

- Patreon Accounts, like Chapo Trap House’s, which generates more than $100,000 a month.

- Kickstarters, like the one that helped revive the DCist after it was shut down by Gothamist CEO Joe Ricketts (who was nominated to be Trump’s Deputy Secretary of Commerce before having to withdraw due to “difficulty untangling his financial assets to meet Office of Government Ethics standards”).

- The Wikimedia Foundation, which received over $91 million from 6.1 million donations last fiscal year, and whose owner recently started WikiTribune, a “community of professional and citizen journalists…reporting, fact-checking, combating fake news, and pulling in enough money from readers to support staff journalists and turn a profit.”

- Non-Profit Educational Resources, like Khan Academy, whose $53,490,148 in income last year included over $5 million from community donors.

- Legal Defense Funds, like the one for fired FBI deputy director Andrew McCabe, which raised $500,000 in its first 48 hours; or Stormy Daniels’, which raised over $300,000.

- QAnon Conspiracy Theorists, like Tracy Diaz, who was able to monetize her “dozens [of] Q-themed videos” to the point she was able to rely “on donations from patrons funding her YouTube ‘research’ as her sole source of income” before having the totality of her videos demonetized by YouTube earlier this month.

Cheese and crepes, there are multiple instances in which, during plugs for the Cash app, my beloved Jon Lovett of Crooked Media will complain about fans using said app to flood him with $1-$2 payments, grousing that “it is annoying having to refund you all.”

What if, instead of watching those dollars fly by like he’s in one of those wind tunnel money booth things, Jon (and John and Tommy and Dan and Erin and Deray and Ana Marie and Ira and Jason) started seizing those demonstrated micropayment opportunities to attain financial independence for Crooked Media?

Maybe they wouldn’t have to keep reading those awkward ads for Tommy Jon underwear, whose smart design and fabrics mean no more pulling at your pant line…

A year after embracing its venturesome micropayment system, the Winnipeg Free Press commands roughly one million visitors per month, and, in addition to its 7,337 digital subscribers and 6,150 activated print subscribers, is selling readers 892,000 articles per month at a very palatable rate of $0.27 per article.

“The biggest benefit we’ve really seen from micropay is that it lowers the commitment,” explains Christian Panson, their vice president of digital and technology, “…that notion that I’m going to be tied to something I’m going to have to cancel later.”

And don’tcha know, those digitally hospitable Canadians even make sure to delay all charges six seconds “in case there is an accidental click,” and every single article is completely refundable “if the reader doesn’t get value out of it.”

If you don’t love everybody, you can’t sell anybody. — Dicky Fox

Yet there is still one, familiar problem with all of the aforementioned outside-the-box, best-of-intentions systems.

That same trickle-down pickle from above…

…which (hopefully) demonstrated how writers and journalists don’t adequately enjoy the fruits oats of their labor, no matter how successful or well-intentioned their benevolent overlords.

The horse constipation metaphor.

I’m an animal for you. — J.M.

Fortunately, there is one simple, purgative solution.

We have to give readers a way to donate to individual writers.

Let them better help us help them.

If we set it up so the parent companies take some agreed-upon cut of the action — even if it’s as much as 99.999% — we could baptize the entire industry in the cleansing waters of a bottom-up, quality-driven revenue stream.

Now, I do get this would bring up all kinds of questions about how to maintain journalistic integrity when creaking open the populist floodgates during the most polarized time in our nation’s history. However, I also know it would beat the current arrangement where we think it’s bravery not lunacy to cling tighter to the rusty blade of righteous reserve as an army of malevolent forces bears down upon us:

And maybe we limit it to soft journalism. Maybe outlets create some sort of economic ombudsman position. Maybe we make the whole process, from user/reader identification to dollar implementation, so transparent that GiveWell blushes.

Regardless, it all goes back to the mantra of the late, great Dicky Fox:

The key to this business is personal relationships.

With an emphasis on “personal.”

Because no matter how strong an outlet’s brand these days, no matter how sterling their reputation, more and more readers are simply following individual writers on Twitter, establishing singular bonds of trust that don’t necessarily translate to those writers’ outlets.

A revealing anecdote courtesy of Emily Bazelon, cohost of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast:

“This is something that’s happened to me a few times in the last, six months, nine months…

I’ll be talking with someone who is not political at all, does not follow news, I have no idea how they vote, and they’ll ask me what I’m working on. And I’ll start telling them about a story, and they’ll say, ‘Oh that’s really interesting, will you send that to me?’ or they’ll go find it and come back to me and want to talk to me about it.

And then they’ll say, ‘Can you send me the other things you’re writing? Because I don’t know what to trust. But now that I’ve met you, I want to read what you are writing.’

I guess it’s a compliment, but I also think it’s nuts!

The fact that you had a conversation with me somehow means that I deserve…it’s like we’re back in a town square where people are talking to each other personally because they don’t know who to trust, and because ‘Oh what’s coming in over my Facebook feed? I have no idea where any of it’s coming from,’ as opposed to ‘here are institutions.’

Sometimes I’ll try to gently say, ‘Well I work for the The New York Times, and you could read other things from the The New York Times,’ and I’ve had people back away from that idea, like, ‘Well, no, I don’t know what to trust in any particular mainstream media outlet, but I want to read you.’

I think it’s not a good sign.”

And not a good sign it may be.

But it’s also our current reality, and to not admit as much is to disrespect the truth we’ve claimed to so revere.

Likewise, for media outlets to not capitalize on this situation is a dereliction of their duty to keep the presses running, excuses be damned.

Instead, we’ve got the New York Times literally removing their writers’ bylines from stories while simultaneously claiming to “put their writers forward as never before.”

Meanwhile, aggregators like Apple News — which has “built a small but powerful news team that is making Apple a key distribution outlet for news publishers” — and Nuzzel — “a Twitter-adjacent aggregation service designed to show you the most talked about links from your feed” — are blatantly attempting to wipe out the concept of brand cachet entirely.

Back in March, when Apple acquired Texture, the “virtual newsstand known as the ‘Netflix of magazine publishing’ that gives readers access to around 200 magazines for a monthly fee of $9.99,” it was all but confirming that they, not the outlets’ individual apps, will be the one who knocks on our phones with endless news alerts.

Certainly, more readers than not will be content to pay their ~$100 a year to The Washington Post for their annual digital subscription and be done with it.

But who knows?

There might just be countless untapped others who’d also be willing to throw David Fahrenthold and his team the same amount they’d thoughtlessly tip a Lyft driver in order to support their award-winning investigative journalism…

Hell, I bet I personally know at least two dozen congressional staffers who’d pony up $10 for Ezra Klein if he ever asked for it, and I guarantee Leon Neyfakh could rake in all kinds of dead presidents for his presidentially incendiary Slow Burn podcast if he ever actively tried to activate the show’s enraptured fanbase.

As I’ve written about before in Goldblum levels of detail, I would slay a whole field of unicorns to know if Grantland could’ve survived with some sort of split-donation, bottom-up system.

Ultimately, it boils down to this one question: why are we not giving our readers the opportunity to give us something more?

Or, in some cases, anything at all?

To paraphrase Wayne Gretzky, you miss 100% of the donations you can’t accept…

…especially the ones that might get slipped in the backdoor.

We are now at a point of transformation with this [industry].

But this is not something to fear, it is something to celebrate. — J.M.

III. Likely Ramifications & Lighthearted Ruminating

Back in my lucrative Creative Strategist days, all my clients would ask the same unanswerable question in some form or another:

“How much is a Like really worth?”

And I, the sly fox, would reply with the same old bit of haughty faux-Buddhist wisdom to assuage them (/justify my agency’s bloated retainer):

“It can be worthless, or it can be priceless.”

Which, bullshitty as it sounds, is nonetheless the truth, my dudes and dudettes.

If a Russian bot Likes your page, it’s worthless; if Beyoncé Likes it, it’s priceless…

But the deeper truth, the one I know we all think about yet fear putting words to, is that we now live in a post-metric world:

Just ask Twitter co-founder and former CEO Evan Williams about Medium’s “Clap hack” problem…

Every digital agency and media company under the sun will obstinately continue to waste processing power trying to make their own ‘fetch’ happen — NBCUniversal has CFlight, ESPN has its own custom standards to measure viewership, the Media Rating Council has proposed its own uniform standard for consumption — yet there is simply never going to be a data-powered silver bullet more valuable than the almighty dollar itself.

In a Washingtonian profile on the post-Bezos acquisition Post there was an interesting aside about how the billionaire owner “was interested in developing custom metrics and the one he fixated on was, as he put it, ‘riveting.’”

I have to assume that’s because it implies inaction, and in this day and age there’s nothing more valuable than our time.

Time is money, as they say…

But then again, so is money.

And if we let it be the one metric we decide to care about most — not traffic, not social shares, not retention rates — it could change everything…

We determine our worth. — Marcee Tidwell

All of a sudden, we’d be able to write for the reader, not their click.

We’d be able to dig in our heels for the long haul, instead of continually pivoting towards the latest short-range shortcut.

That awful writing technique journalism school teaches where readers have to essentially already know what’s going on to understand what’s being reported would be replaced by a type of reportage that zealously wanted its readers to absorb it.

The editor would most likely find a resurgence in a world where alchemy was golden — “I’d want to go somewhere I felt there was a pungent, strong editor who could teach me things,” asserts the renowned Tina Brown — and ay Dios mio, there’d be an immediate ESPN Deportes-ification of every article on the internet as outlets tried to maximize their reach, advertising-friendly demographics be damned.

We, as an industry, would finally begin aspiring for the quan…

It means love, respect, community, and the dollars too.

The entire package.

The quan. — Rod Tidwell

We would start designing for our readers instead of our advertisers, and treating our pages like the sacred vehicles they were always supposed to be.

We’d end the abusive practice of interrupting our arguments with intentional distractions…

…which if replicated during a televised news report would instantly be called out for the insulting rhetorical Tourettes it is.

We’d make it as easy as possible for our readers to act on our calls-to-action…

…so potential subscribers aren’t “taken to a page with no options to get a newspaper, until [they] discover the super-secret ‘subscribe’ button hiding in the upper-right”:

We would commit ourselves to more interactive investigative pieces, like The New York Times’ arresting “America’s New Ellis Island” and CityLab’s examination on “How the Other Half Eats.” There’d be more visually dynamic articles, like HuffPost’s Highline piece on “Poor Millennials” and ESPN’s “Perfect NFL Roster.”

Concordantly, New York Magazine wouldn’t dare publish a 6,000-word piece on “The Most Important Video Game on the Planet” without putting some sort of embed in the digital version so as to show what Fortnite’s gameplay is actually like, and The Washington Post wouldn’t put together a huge piece on “The top 25 memes of the web’s first 25 years” without inserting a single GIF:

Don’t worry, I fixed that one for them…

But the point remains.

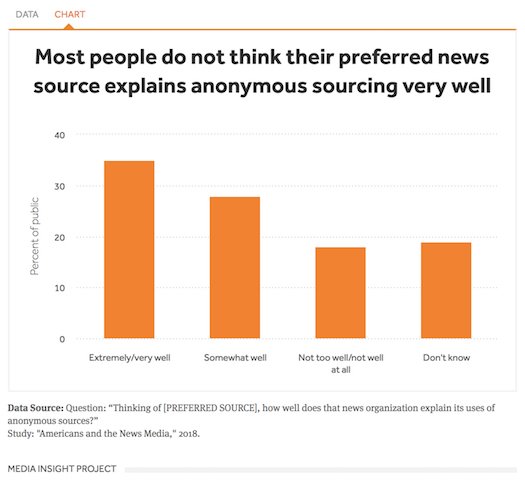

If dollar-worthy quality becomes our guiding metric, it might motivate outlets to invest more in the development of nifty innovations like the Globe and Mail’s expandable, in-article explainers and the BBC’s handy in-article chat bots that are destined to get ripped off by every other major outlet once the industry internalizes that 43 percent of adults say they don’t really know what the term “attribution” means and 42 percent are either unsure what an anonymous source is or believe the journalists themselves do not know the source’s identity.

More newspapers might also take the time to publish something like The New York Times’ enlightening “Understanding the Times” series in order to better ingratiate themselves to their readers (/explain why Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio made a complete ass of himself when he tried to vilify the objective act of journalism as “fake news”).

At the moment, according to the American Press Institute, only 35 percent of people say their favored news organization does a good job explaining its use of anonymous sources…

…and just 12 percent of journalists think the public has a strong grasp of the difference between an editorial and a news story.

And yet we continue undeterred; heedlessly locking up our best content behind paywalls, hoarding work supposedly created for the common good behind digital barricades only the most privileged can infiltrate.

Besides, as Franklin Foer (current correspondent for The Atlantic and former editor of The New Republic) reminded The Nieman Journalism Lab’s Hope Reese in a conversation last October, “Even when the Times imposes paywalls, they’re still not really asking very much of consumers relative to the resources that are required from consumers to fund journalism on that scale.”

“Everything is out of whack right now.”

Over the past half decade, our readers have figured out how to share passwords — same as they do with Netflix and HBO and Hulu — and use Incognito Mode, which can (still!) get one behind a fair amount of mainstream media’s paywalls. And if neither of those options work, readers are just as likely to move on to the next thing tab as they are to cough up any paywall-razing dinero, considering there are currently roughly 80 million posts published on WordPress every year, which are themselves competing for their attention against the approximately 450,000 tweets, 46,740 million Instagram posts, 990,00 Tinder swipes, 16 million text messages, and 400 hours of new video on YouTube thrust into the world every minute.

Basically, there are two things we can always count on: money in the banana stand, and some other thing equally deserving of our reader’s time.

That’s why, in the words of The New Yorker’s Alan Burdick, “We must begin to write for the infinite.”

However, for that to happen, there needs to be something that financially incentivizes writers to focus more on evergreen content as opposed to chasing that elusive buzz known as “newsworthiness,” something that utilizes game theory to dragoon outlets into creating enduring resources (e.g., Vox’s card stacks, POLITICO’s explainers, The Ringer’s Rewatchables series) at the expense of the transient and the disposable.

We live in a cynical world, a cynical world. And we work in a business of tough competitors. — J.M.

Across the Atlantic, the Swiss newspaper Le Temps has already developed an ingenious algorithm they’ve named “Zombie” that recommends a daily list of articles from the past that fit again in the news cycle…

…yet those resourceful Swiss journalists still don’t have a way to reap anything more than ad revenue and good will from their innovative utility.

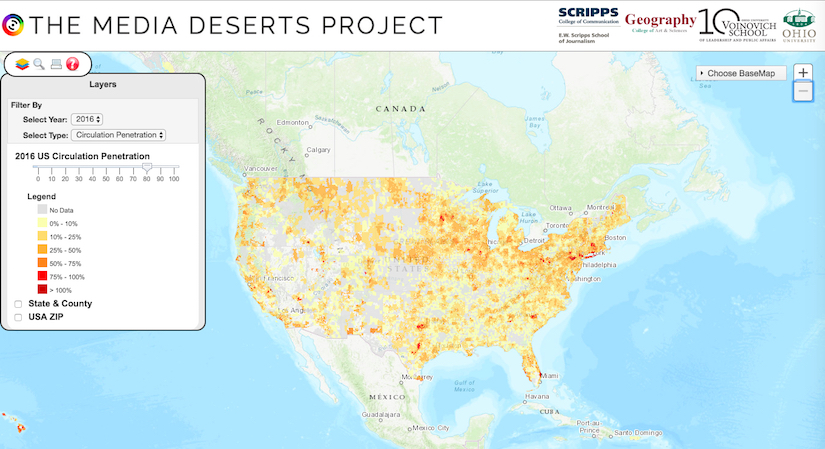

Similarly, think of how many local newspapers could thrive survive if they made it easier to monetize their altruistic, emotionally-invested audiences…

Researchers at Duke University released a report earlier this month that found across 16,000 news stories, gathered over seven days, across 100 U.S. communities not situated in major media markets, “only about 17 percent of the news stories [were] truly local” (i.e., “about or having taken place within the municipality”), and just 43 percent of the news stories provided by local media outlets were actually produced by the local media outlet itself.

If you want to know what that looks like, take twenty seconds to play with this interactive map of the country’s media deserts:

Report for America has said they aim to put 1,000 journalists in those understaffed newsrooms by 2022 to help alleviate the situation, with one of the project’s founders explaining to The New York Times that “people are applying for the same reason people want to go into the Peace Corps: There’s an idealistic desire to help communities, and there’s a sense of adventure.”

“They want to try and save democracy.”

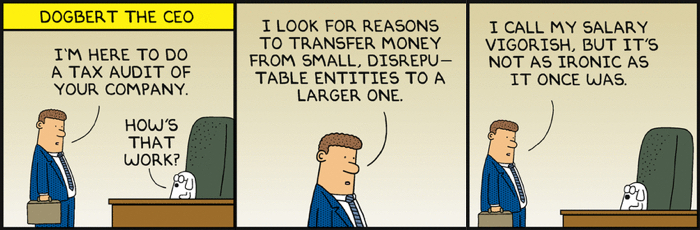

Yet there is currently no way for our democracy to support those brave souls other than to give to Report for America directly and pray enough of the cash makes its way through the administrative filter and bureaucratic vig that comes with any formal organization.

Likewise, when the Mendocino Voice saved countless lives by updating residents almost around the clock about shifting evacuation zones, services for the displaced, and efforts to contain the raging fires enveloping their community, those integral town criers had no way to capitalize on the more than 76,000 Mendocinans relying on their work; resorting to asking readers who’d just lost everything to commit to a monthly membership.

Again, math isn’t my strongest suit, but it seems like if someone appreciates The Mendocino Voice enough to give them $3 a month, there’s a decent enough chance they’d be compelled to give the same — if not more — if simply given the option to one-off donate instead/as well. And if the Voice can get even a single $5 one-off donation (or five $1 donations) out of said hypothetical indebted reader each month, it’s now almost doubling its per-reader revenue.

It’s the journalistic equivalent of the Houston Rockets realizing it makes more sense to shoot 3s and miss 65% of the time than attempt 2-pointers and miss 55% of the time:

Plus, with this kind of revenue system in place, outlets could experiment with a whole new type of marketing…

Instead of depending wholly on a sales team peddling the wonders of an annual subscription, they could start apportioning some of their staff to concentrate on what I like to call “post-publish marketing.”

An example:

When one of the best pop culture writers I know, Charles Bramesco, wrote about “The fearless pessimism of Netflix’s BoJack Horseman” for my old outlet Random Nerds, we weren’t content to just tweet it out with an @ and a #.

We went on IMDb, found the most accessible (/unknown) producer of the show and tweeted it directly at him. Then, when he inevitably responded with glowing approval, we went to Reddit and were able to say to the 169,000 members of r/BoJackHorseman, “Hey, one of the producers is hyping this great article about the show. Check it out!” and scoop up tens of thousands of views and a few handfuls of one-off donations.

And it’s not only Reddit, which outlets like The Washington Post are finally starting to come around to, that can be harnessed for this kind of thing. Vox is killing it when it comes to their Facebook groups, The Atlantic’s product team developed a Chrome extension that displays a piece of Atlantic journalism every time you open a new tab, and some of the braver outlets are even daring to explore the murky depths of Tumblr.

Good lord, if I had the time and means, I would love to try taking a page out Suraj Patel’s playbook…

The (since-defeated) Democratic candidate who sought to represent the 12th Congressional District of New York “waged the most millennial of campaigns” by having campaign volunteers log onto Tinder, Grindr, and Bumble with the explicit intention of essentially catfishing their matches.

“Mr. Patel calls it Tinder banking: Participants set up an account with a picture of an attractive person, usually not themselves, and begin seeking matches.”

In other words, with only a few iPhones (and a complete disregard for ethical marketing), his bootstrapped operation was able to compete with incumbent Carolyn Murphy’s professionally staffed and exponentially more well-funded campaign.

Their leanness became their strength.

The great ones all do one thing at the time of their greatest success.

They change the game.

They make it harder for themselves. They raise the bar.

They work not just harder, but they work smarter. — J.M.

It’s the same mindset that helped Dave Portnoy turn his Barstool Sports side hustle into a modest media empire, and college dropout Kyle Taylor go from penny hoarder to Penny Hoarder, and Ben Thompson shepherd Stratechery from a personal newsletter to an invaluable compendium.

The Ken, out of India, publishes just one story per day, and it’s currently pulling off charging “as much as subscribing to two of India’s leading business newspapers, The Economic Times and Mint.”

Celebrating its latest $1.5 million in venture money, co-founder Rohin Dharmakumar explained that he’d “had enough conversations and email exchanges with hundreds of [readers] to know they value depth, analysis, and an informed point of view over mere quantity.”

Speaking of, allow me to share one of my favorite self-evident theories: “The 1,000 Fan Theory.”

First postulated by tech writer Kevin Kelly back in 2008 — well before crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo had taken off — the 1,000 Fan Theory “in its most basic terms explains that if someone can get 1,000 people to give them $100 a year (whether in profits or donations), they are then making $100,000 a-year.”

I know, it sounds so basic it’s almost stupid.

But it’s almost stupid like a fox…

As Kelly himself writes, “Here’s the thing; the big corporations, the intermediates, the commercial producers, are all under-equipped and ill suited to connect with these thousand true fans. They are institutionally unable to find and deliver niche audiences and consumers. That means the long tail is wide open to you, the creator. You’ll have your one-in-a-million true fans to yourself. And the tools for connecting keep getting better, including the recent innovations in social media.”

“It has never been easier to gather 1,000 true fans around a creator, and never easier to keep them near.”

Yet, for some reason, over a decade later, when crowdfunding has given us everything from Cards Against Humanity to the Veronica Mars film, the industry best equipped to implement that kind of creator-driven, crowdsourced system has actively rebelled against it.

Pew Research Center reported last year that 93% of adults in the U.S. get at least some news online. That is roughly 302,901,000 people. If you’re telling me we can’t find the sliveriest sliver of that 300 million to balance out our ever-shrinking operating costs, then maybe we deserve a knockout blow.

The Jack Shafers of the world may piss and moan about how they “[don’t] want [their] favorite hacks turned into marketers,” as he wrote in response to NYT columnist Nicholas Kristof’s public letter from last November asking Times readers to help financially underwrite their unparalleled “investigations of corruption, of foreign influence in U.S. elections, of breakthroughs in science in health.”

However, the Jack Shafers of the world are also 61-year-old Libertarians who loftily believe in a “much smaller government, much lower taxes, an end to income redistribution…fewer guns laws, [and] a dismantled welfare state,” so who really gives a flying fork if those ever-less-relevant sexagenarians think it’s “pathetic” to “grovel” for financial assistance?

(BTW, congrats, Jack, on winning the Arthur Rowse Award for Press Criticism for your “timely and original takes on the conflict between the press and the Trump White House” the exact same day I wrote this section!)

That part about how we should embrace what is still virginal about our own enthusiasm and force open the tightly-clenched fist of commerce and give back a little for the greater good…

I was inspired, and I’m an accountant! — Dorothy Boyd

Shafer tries to claim his relationship with Times journalists is “more like my relationship to the station manager of the subway — he’s just another interchangeable employee producing a service,” but the fact the august author knows Kristof’s name is proof that isn’t the case (unless Jack is on a first-name basis with his neighborhood subway manager).

He may try to compare Times writers to “waiters, airline attendants, hotel desk clerks and other public-facing employees” because they’re ‘fishing for tips,’ but he also claims that “indispensable coverage and analysis” is all the Times needs to stay afloat, even as he belittles its staff by deeming them easily replaceable (and with the Times’ financial reports proving otherwise).

Not to mention, if these staffers are so replaceable, then why are live events where subscribers can intermingle with these very reporters and editors becoming one of the most successful forms of reader engagement out there?

News Revenue Hub’s COO Christina Shih, whose job is to know her stuff when it comes to this stuff, is screaming from the digital rooftops that “benefits that connect your members with your core product, your editorial content, deepen the relationship you have with them and will increase their propensity to give again.”

There’s a pragmatic reason we’re seeing such a surge in “a behind-the-scenes look at your favorite media outlet” as entertainment products, from The New York Times’ four-part 2018 documentary on Showtime to Buzzfeed’s weekly series on Netflix.

Readers want to engage with the men and women behind the words.

As Liz Garbus, the documentarian behind The Fourth Estate put it, these organizations “[understand] that at a time when journalism [is] under attack from the highest powers in the land, it might not be a bad idea to show the public exactly what it is that real journalists actually do.”

I’m the guy you don’t usually see, the guy behind the scenes. — J.M.

Maybe the Times is jumping the shark with its “gimmicky ventures such as around-the-world trips by private jet (for $135,000 a person) in the company of Times journalists,” but, much like how sports team owners figured out they could milk their wealthiest season ticket holders for even more cash by inventing the “personal seat license,” it could be considered financially irresponsible for the Times to not get it while the getting is good.

Regardless, if live events are the next great revenue stream, let’s embrace it.

I personally had the privilege to watch that straight-shooter respected on both sides Jon Lovett go from filling the 1,200-person Lincoln Theatre in June of 2017, with tickets going for $35, to selling out the cavernous 6,000-person Anthem just five months later, with tickets going for $49.50-$125.00 (before service fees).

Local outlets can get in on the action, too…

The Coloradoan — a part of the USA TODAY network that covers the greater Fort Collins area — has a daily circulation of only about 11,000. However, it’s found immense success participating in USA TODAY’s Storytellers Project, which features “journalists curat[ing] entertaining, true stories from neighbors and notables, told live in front of diverse audiences,” and organizing its Secret Suppers series, which features “dinners held in unique, surprising locations [in order to] introduce a diverse group of community members to talented chefs in foreign-but-intimate settings.”

According to their news director, Eric Larsen, these events “have generated more than $30,000 in ticket revenue,” with twelve of them having sold out so far.

Pop-Up Magazine, the live event series that features “true, never-before seen or heard multimedia stories performed on stage by writers, radio producers, photographers, filmmakers, and musicians,” has seen its audience grow tenfold since its launch in 2014:

During a recent Q&A with Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett asserted that “only perhaps the New York Times, WSJ, and Washington Post have a digital product with robust enough revenue to be viable over the long-term,” so it really is on us to find other ways to make our journalistic ends meet.

The question is, how do we personalize that machine? — J.M.

It could be as simple as printing more t-shirts; like Crooked Media’s “Friend of the Pod”” one that’s become the unofficial uniform of the Resistance, or Minnesota Public Radio’s opportunistic “#MPRaccoon” that took advantage of a viral building-scaling raccoon, or The Ringer’s Curry-approved “Blog Boys” design that honors a bit of impromptu analytic wisdom courtesy of his Warriors teammate Kevin Durant…

Or, maybe we start chocking our copy full of affiliate links, which while a somewhat tisk-tisked practice is frankly only as underhanded as one chooses to make it.

Sure, if you’re deceitfully writing entire articles just so you’ll get a cut of that sweet, sweet Amazon money (*cough Refinery29, Buzzfeed, Brain Pickings cough*), then yes, you’re as treacherous as the inhabitants of Antenora and should await your eternity frozen in the ice of Cocytus.

If, however, you’re actually transparent and truly pure of heart when it comes to with whom you’re affiliating (e.g., Wirecutter, This Is Why I’m Broke), then there’s ultimately no reason for flagellation and the second sphere of Paradiso is yours to inhabit.

Or, we can get a little more creative…

The New York Times has been successfully charging $40 a year to access its (very useful) cooking section, but it also recently decided to let readers — not just subscribers — customize their own personal physical cookbook (in soft cover for $35, or hardcover for $55); an obvious but effective rip-off of Buzzfeed’s own Tasty collection, which itself racked up racks last summer with its Tasty-branded, tablet-friendly hot plate that’s “designed to follow recipes from the Tasty cookbook.”

Meanwhile, The Wall Street Journal has their wine club that partners with “the world’s leading direct-to-home wine merchants” (and which has got to piss off the Wincs and Tasting Rooms of the world), while Bloomberg has their notorious “dedicated data terminals for bankers, traders and money managers.”

By all means, I’m not saying we go full Alex Jones and start mongering everything under the sun —

— or have our interns run around major cities charging those bane-of-my-existence electric scooters for a few bucks a pop.

However, there is something to be gleaned from The Minneapolis Star Tribune’s addition of “in-app purchasing to its mobile apps,” and Seattle’s KUOW exploration of Alexa as a potential fundraising source, and the ACLU’s unconventional creation of an Amazon Dash Button that donates $5 to them whenever you push it (/“whenever Trump tries your patience”).

Then there’s always the high-risk, high-reward world of cryptocurrency…

The Pirate Bay has been experimenting with cryptomining for a while now, embedding a miner that utilizes 20-30 percent of their visitors’ CPUs’ processing power to mine Monero in an effort to “get rid of all the ads” while still making “enough money to keep the site running.”

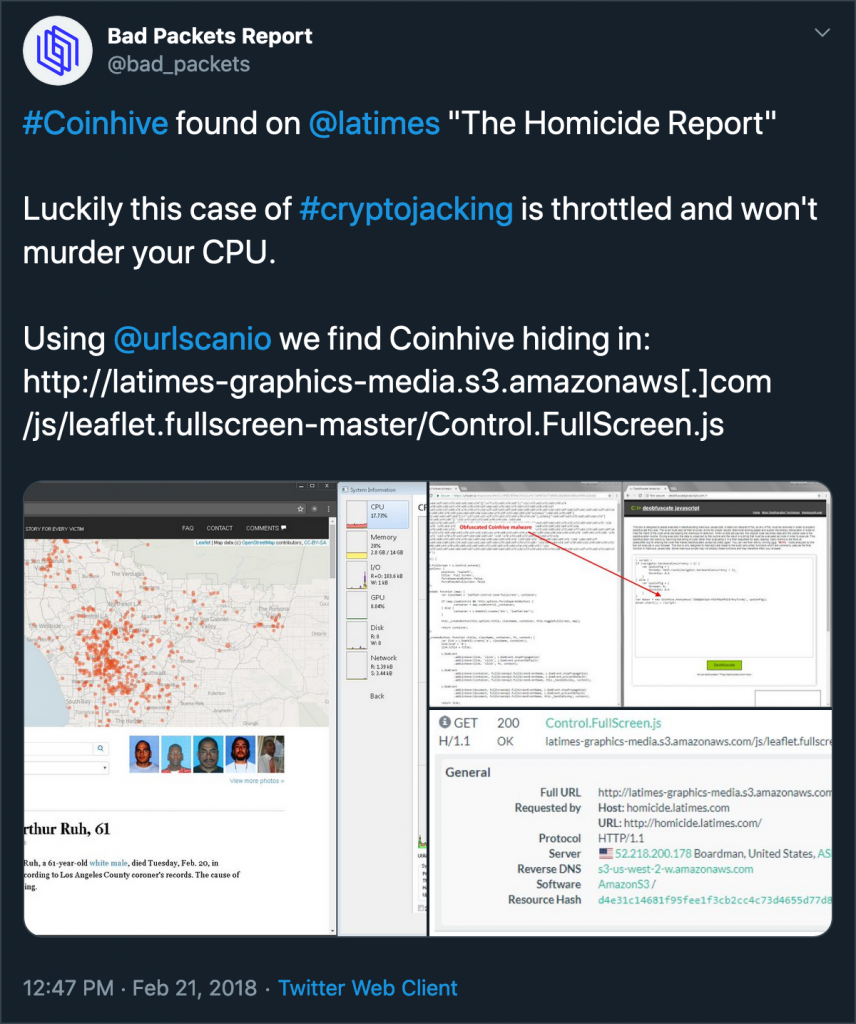

And if that sounds too Orwellianly invasive, go ahead and read up on how legitimate journalistic enterprises like The Los Angeles Times’ Homicide Report are already getting hacked to do the same kind of thing, with cyber attackers leveraging the Coinhive mining platform to profit off of Los Angeles Times readers without them, or the outlet, being any the wiser:

Concurrently, we’ve got the Brooklyn-based media company Civil betting the encrypted bank on the inevitable fruitful integration of cryptocurrency and journalism, having created what they describe as “a global platform for independent journalism, powered by blockchain technology and cryptocurrency, governed by an open-source constitution.”

Who knows if it, and its token-based system, will work — especially if there’s “a really hard quiz” involved — but to be honest, I’m just glad the writers and editors who were forced to jump off the sinking ship known as The Denver Post have found at least a foster home for their recently announced Colorado Sun experiment hosted on the aspirational platform.

You knew things were getting bad over at the Post when their unfathomably incompetent, comically evil hedge fund owners thought it would be a good idea to (also) completely lay off the staff from the paper’s groundbreaking marijuana news vertical The Cannabist even though it was “luring more readers than veteran publication High Times.”

If you’re really that strapped for cash, why not try following in the sticky icky footsteps of such high-minded celebrities as Willie Nelson and Whoopi Goldberg, Snoop Dogg and Tommy Chong and cultivate a “Cannabist’s Choice” signature weed strain, which I’d bet my stash would bring in a few quick zips of green for Ricardo Baca and his team.

It’d be better than having yet another respected outlet go up in smoke…

IV. In Conclusion…

If you, person still reading this, are one of those who have “ever wondered about the drawbacks of being quiet about important things.”

Or questioned how we’ve let it become “too easy to say ‘later’ because we all believe our work to be too important to stop.”

Yet you still, somehow, believe “this great lost art will never truly die [because] putting words to paper is a sacred thing,” then join me in loving this industry birthed to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable enough to not let it die, not like this.

I think perhaps truly loving something is the ability to love it at that moment. — Dorothy Boyd

To pinch the closing lines of The Things We Think and Do Not Say:

I have now written far too much on the subject of our future, the future of this business. But the beauty of this proposal, I think, is that it is only a slight adjustment, an adjustment in our minds. An adjustment in attitude. An adjustment to point where we can discuss the things that really matter to us…

And if I am wrong, then grab me by the collar and tell me why you disagree. And I will happily talk with you because we are talking about something that matters.

Comments are closed.