As much as I hope you read the words below, one of the central reasons I put this piece together was to establish a library for all the Twitter-friendly GIFs I’ve made (so far). Feel free to take them. Share them far and wide. They’re all yours, internet.

(I also have them in larger sizes and at higher resolutions; hit me up on the Twitter if you want them.)

***

On August 7, 1930, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith were snatched from the Grant County jail cell they had been thrown into the night before, remorselessly beaten, repeatedly stabbed, and then ceremoniously hanged from a large poplar tree in Marion’s courthouse square.

A crowd composed of some 5,000 attendees flocked to take in the spectacle, enjoying the chance to socialize on a humid Thursday evening in their sleepy Indiana town; for it wouldn’t be until the following afternoon that they would realize everything had changed, just then, right before their very eyes. That this particular lynching was unlike any of the thousands upon thousand upon thousands before it. That local studio photographer Lawrence Beitler had taken a lynching photo so instantly iconic he would have to work ten days straight to print the number of copies demanded of him by his white patrons, who were fond of using lynching photos as postcards.

So iconic it would inspire Jewish poet Abel Meeropol to write “Strange Fruit” — which two years later would be transformed into a protest anthem so stirring it is now considered “a declaration of war . . . the beginning of the civil rights movement”:

On September 3, 1955, in Chicago Illinois, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley held an open casket funeral for her 14-year-old son Emmett, so her country would have to reckon with the sight of his mutilated body.

“There was just no way I could describe what was in that box. No way. And I just wanted the world to see.”

An image from the funeral, taken by a man named David Jackson, of “a stoic Mamie gazing at her murdered child’s ravaged body,” would go on to be named one of TIME‘s Most Influential Images of All Time:

On March 3, 1991, a plumber named George Holliday stood on the balcony of his apartment near the intersection of Foothill Boulevard and Osborne Street, clutched his brand new Sony Handycam, and filmed, for nine minutes, as a group of Los Angeles Police Department officers struck an unarmed black man with batons “between fifty-three and fifty-six times.”

At his friends’ urging — and after being rebuffed by the LAPD — Holliday decided to give the tape to local television station KTLA, which aired a 24-second long clip of it during the next evening’s broadcast, igniting “one of the most-devastating civil disruptions in American history:

On January 1, 2009, a handful of train passengers used the 2.0 megapixel cameras at their disposal to capture the exact moment when a .40 bullet fired from BART Officer Johannes Mehserle’s gun pierced the back of 22-year-old Oscar Grant, exited through his front side, and ricocheted off the concrete platform of Fruitvale Station, puncturing his lung and ultimately killing him.

Within hours, one of those cellphone-wielding passengers passed along the footage, anonymously, to KTVU:

“When people tell the story of Black Lives Matter, they either start it in 2014 with Mike Brown, or they start it in 2013 with Trayvon Martin. But for us, right, for those of us who created Black Lives Matter, it really does kind of start with Oscar Grant.” — Alicia Garza, co-founder of Black Lives Matter

Since that infamous New Year’s Day in Oakland, previously-helpless eyewitnesses have weaponized unassailable film to force Americans to learn what it looks like when a 12-year-old boy is shot while playing in the Cudell Recreation Center in Cleveland; what it looks like when an officer fires five rounds from a Glock 21 into a fellow human’s back before attempting to frame him; when a father of four bleeds out in a Wendy’s parking lot; when a dying man cries out for a mother no longer living; when someone can’t breathe.

What it looks like when the people who are supposed to protect us are who we need protection from…

What it looks like when an officer goes out of his way to pull down a protestor’s mask before pepper spraying him in the face…

When they use the same knee-to-neck technique that killed George Floyd…

When even a sitting member of Congress is shown to not be exempt from the abuses of power…

Thanks to the arsenal of modernized Sony Handycams we keep holstered and at the ready, when a video of an NYPD SUV running over a crowd of protestors goes viral —

— we can show it is not just an anomaly, a bad apple, a one-off incident by a scared cop.

It’s happening from coast to LAPD-controlled coast:

When officers blatantly disregard their department’s protocols and discharge “non-lethal” rounds from moving vehicles —

— we can expose that blatancy.

And the kind of damage those “non-lethal” rounds can do:

Even though Minnesota state troopers have already confessed to slashing the tires of cars belonging to protesters and journalists on two separate nights, it truly does take seeing the multiple videos and photos of those officers, decked out in their military-style uniforms, puncturing tires with their knives, to accept something like that can take place on American soil. Even if one reads all about the recent phenomenon of NYPD cruisers terrorizing the residents of Harlem and Crown Heights by blaring a racist jingle as they drive through those neighborhoods, it’s another to see, and hear, such eerie scenes.

Just last week, hundreds of law enforcement officers, who have worked at every level of law enforcement, “from tiny, rural sheriff’s departments to the largest agencies in the country,” were revealed to be members of anti-Islam, anti-Black, or anti-government militia Facebook groups.

As I write this, it’s being reported that three police officers in Wilmington, North Carolina have been fired after their department discovered patrol-car video of conversations containing violent, racist comments — including an instance when one Officer Kevin Piner tells Corporal Jessie Mooren that society needs a civil war to “wipe ’em off the fucking map. That’ll put ’em back about four or five generations.”

Nevertheless, for some, the lucid reality that not all cops are knights in shining Kevlar armor needs more than digital ink on a screen to be accepted.

They need see for themselves why Officer Steven Pohorence of the Fort Lauderdale Police Department was recently suspended (with pay):

They need to see for themselves those six Atlanta police officers baselessly smash 22-year-old protestor Messiah Young’s driver side window, tase him, and drag his still-spasming body out of his car to understand why those half-dozen cops were charged with aggravated assault:

They need to see just how hard since-charged NYPD Officer Vincent D’Andraia had to push 20-year-old protestor Dounya Zayer for her to have to be sent to the hospital with a concussion:

They need to see 75-year-old Martin Gugino fracture his skull on the pavement in front of Buffalo City Hall after being pushed by BPD Officers Aaron Torgalski and Robert McCabe. And the officers who don’t give the pooling blood a second glace:

Even in the moment, it was unfathomable to think that in our nation’s capital, nameless throngs of law enforcement officers would follow the orders of Attorney General Bill Barr and, at the edge of the square at H Street NW and Madison Place, unleash a violent, indiscriminate furor on their fellow Americans:

That evening, hovering just tens of feet above the streets of Washington, D.C., multiple military helicopters used “show of force” maneuvers to create wind speeds equivalent to a tropical storm. “Broken glass scattered in the air around storefronts, while protesters ran to find cover, shielding their eyes. The sound of the rotor drowned out everything else.”

The following day, John Allen — the former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan — would write that the government’s response to the protests may well have signaled “the beginning of the end of the American experiment.”

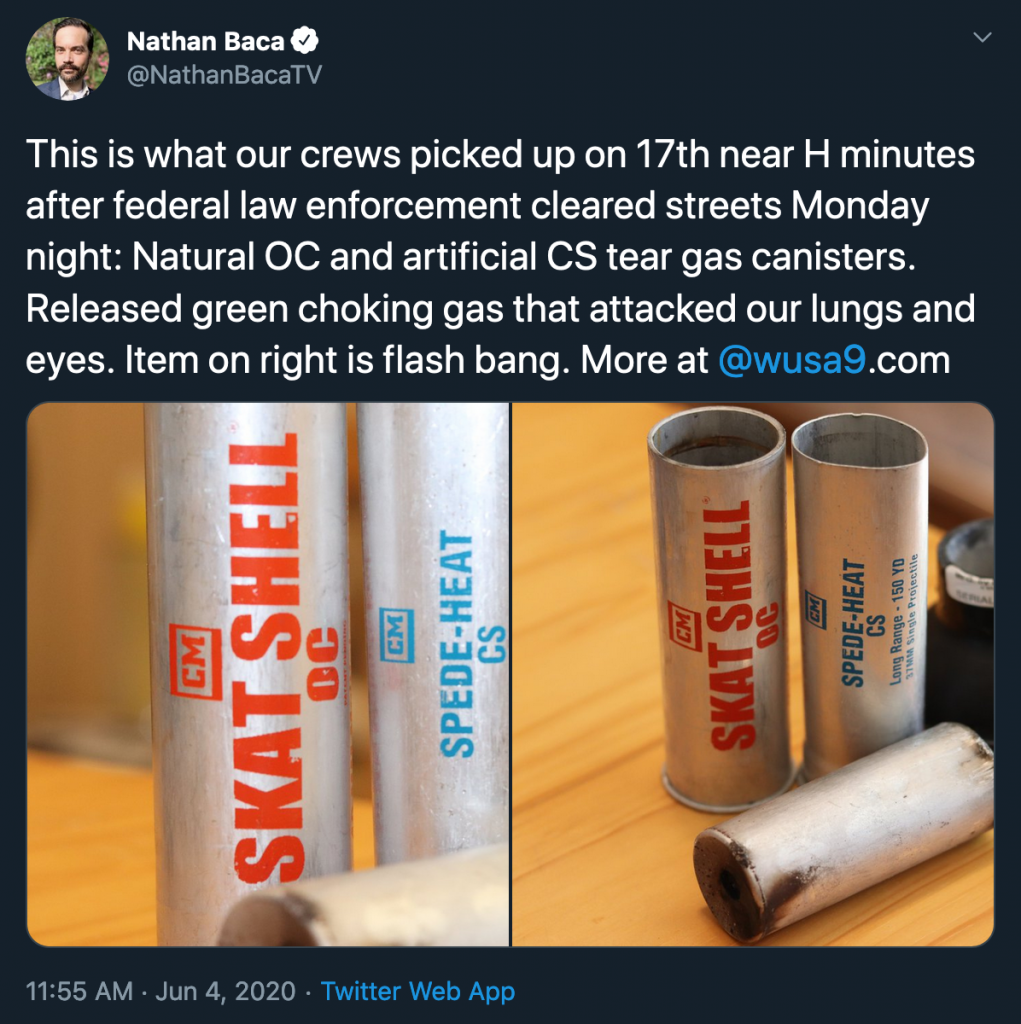

The U.S.Park Police has vehemently denied using tear gas, a tactic prohibited under international law. But Nathan Baca can show you photos of the canisters of chloroacetophenone and chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile he picked up on 17th Street:

Law enforcement agencies have denied or declined to say whether they needlessly shot paint canisters at Minneapolis residents who were simply standing on their porches (after curfew). But Tanya Kessen happened to be filming when one of her housemates got shot with a green paint canister “right on the fucking crotch” after one of those officers yelled, “Light ’em up!“:

Government officials have been disdainfully adamant that journalists aren’t being specifically targeted. But Scott Nover of Pressing has put together a spreadsheet documenting the incidents of press freedom abuses (so far), and the tally has already surpassed twice the number the U.S Press Freedom Tracker typically documents per year.

The first night of the protests, JC Reindl, a reporter for the Detroit Free Press, was pepper sprayed in the face, after showing the police his media badge. Mere feet away, his colleague Kelly Jordan had her camera slapped out of her hand by a masked police officer as she tried to capture the grotesque scene:

Michael Anthony Adams of Vice, holding his press card aloft, was hit with multiple foam baton rounds, forced to the ground, and then, while being held down, pepper sprayed in the face; press card still in hand:

During a live broadcast, a riot gear-clad U.S. Park Police officer assailed Australian cameraman Tim Myers so maliciously Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne has demanded the U.S. formally investigate the incident:

During a live broadcast, a Louisville Metropolitan Police Department officer fired pepper balls directly at AVE 3 News reporter Kaitlin Rust and photojournalist James Dobson as they were covering a protest in downtown Louisville:

During a live broadcast, Minneapolis state troopers arrested CNN corespondent Omar Jimenez and his crew on such scrupulous charges they were released less than an hour later (with an apology from the governor):

USA TODAY staff reporter/photographer Andre Lamar streamed his own arrest on Facebook Live. Des Moines Register reporter Andrea Sahouri recorded a testimonial of her arrest from the back of a police transport vehicle and posted it to Twitter. When the NYPD arrested HuffPost‘s Christopher Mathias, it was under a flood of camera lights.

Tom Aviles, a veteran photojournalist with Minneapolis’ CBS affiliate, filmed himself being shot with a rubber bullet before state patrolmen arrested him. A Reuters TV crew kept rolling even as they were getting fired upon. Mollie Hennessy-Fiske of the Los Angeles Times recorded a video while sitting at the Minneapolis police station to describe in detail what it was like when she and a dozen other journalists “shouted ‘press’ and waved credentials but were nonetheless cornered and chased by police spraying tear gas and firing rubber bullets.”

According to the Associated Press, more than 10,0000 protestors have been arrested since George Floyd’s death.

Countless others have been beaten, kicked, shot, tased, pepper sprayed, and legitimately physically threatened by all-too-eager, heavily-armored members of law enforcement.

But, lordy, there are tapes…

…and, lordy, are they working.

As Sarah Fischer of Axios recently put it, “Twitter has become the nerve center of the American news cycle,” with around seven in ten adult users in the U.S. getting at least some of their news there. Earlier this month, the platform saw the most per-day downloads in the company’s history, with ~670,000.

When Jordan Uhl edited a two-minute supercut of police brutality and posted it to Twitter, it amassed more than 50 million views in mere days. And when he, keenly and selflessly, posted a Dropbox link so anyone could download and share the video, it immediately spread to Instagram and TikTok.

In the span of a month, there were 1.04 billion social media interactions on stories related to police conduct, police reform, racial inequality, Black Lives Matter, and the cases of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery.

In the span of a month, we’ve seen police chief resignations, the banning of chokeholds and no-knock warrants (in a few locales), the repeal of 50-a (which allowed police to shield misconduct records), and the defunding, in some cases even dismantling, of police departments.

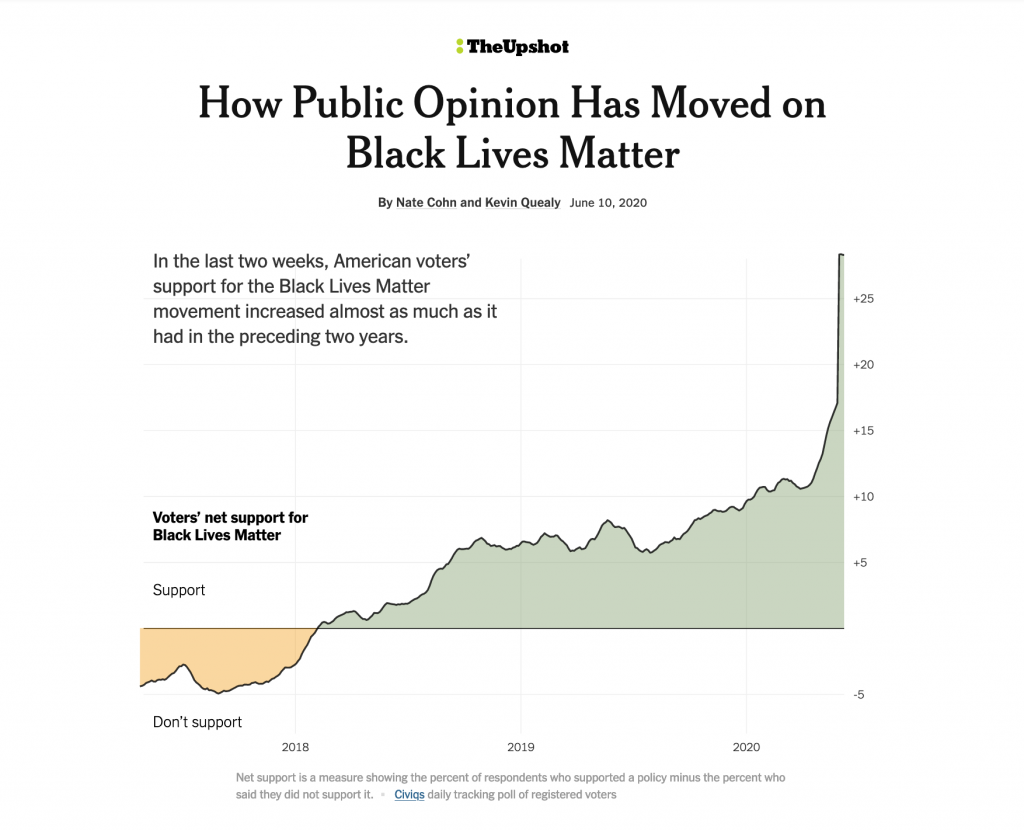

Since George Floyd’s death, the percentage of Americans who believe our country’s police system is “basically sound and requires essentially no changes” has plummeted to 7%, while support for the Black Lives Matter movement has increased almost as much as it had in the preceding two years.

Meanwhile, “a deluge of online donations has washed over organizations big and small — from legacy civil rights groups to self-declared abolitionists seeking to defund the police.” Bail funds alone have received $90 million. Money has come in so quickly, and so unexpectedly, that some of these groups have begun redirecting would-be donors elsewhere.

Which is all to say, keep going.

Keep fighting. Keep protesting. Keep recording. Keep posting. Keep sharing.

“Seven years ago, people thought that Black Lives Matter was a radical idea. And yet Black Lives Matter is now a household name and it’s something being discussed across kitchen tables all over the world.” — Alica Garza

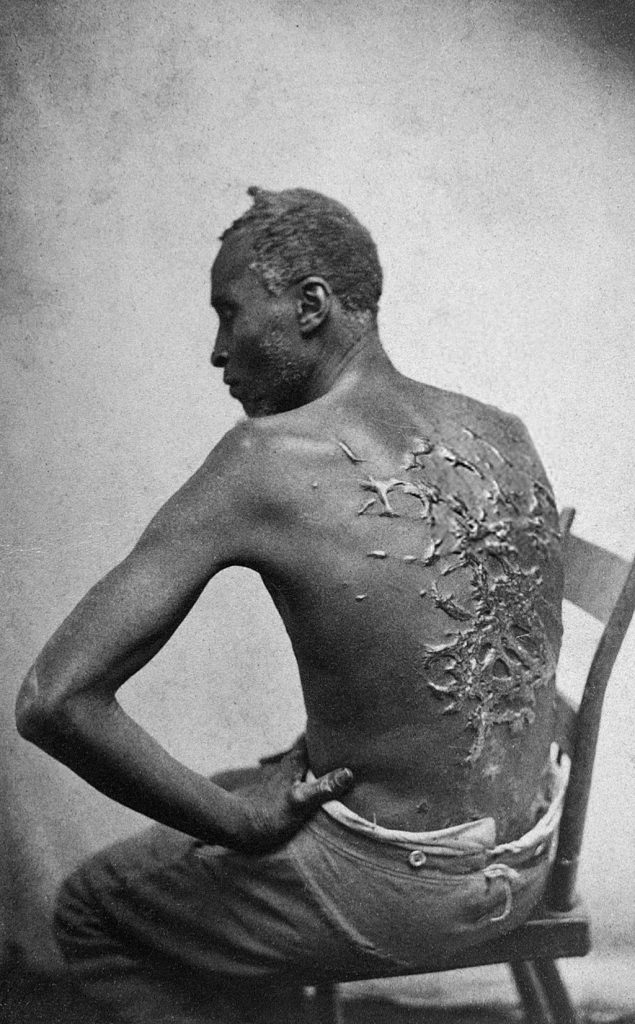

In March of 1863, an enslaved African American named Gordon escaped from the 3,000-acre Louisiana plantation of John and Bridget Lyons and headed east towards the Mississippi River. For ten days, he crossed every creek and waded through every swamp he could find, hoping to throw off the hounds. He’d even regularly rub his body with onions he had pilfered before he left.

Some 36 miles later, Gordon finally made it to the Union Army camp just outside of Baton Rouge, where soldiers of the XIX Corps were stationed. After being taken in and fed, he was given a full medical examination, which happened to be attended by two itinerant photographers, William D. McPherson and J. Oliver, who were touring the camp.

The photo they took that day, of the trenchant scars defiling Gordon’s back, would go on to be one of the most impactful images of their century:

In a letter to his brother, the surgeon of the First Louisiana regiment enclosed a copy of the photograph, adding:

I send you the picture of a slave as he appears after a whipping. I have seen, during the period I have been inspecting men for my own and other regiments, hundreds of such sights—so they are not new to me; but it may be new to you.

If you know of any one who talks about the humane manner in which the slaves are treated, please show them this picture. It is a lecture in itself.

***

RESOURCES:

- “A criminal justice expert’s guide to donating effectively right now” by Dylan Matthews, Vox

- “12 Ways to Be a White Ally to Black People” by Janee Woods, The Root

- Stand Up for Racial Justice’s various toolkits

Comments are closed.